How “Rent” Changed Broadway

by Ashley Griffin, Guest Editorial

To read the earlier parts of this series, click below:

In the 1980’s…Broadway was dead.

People had said it before, and they would say it again, but in the ‘80, full-on rigor mortis had practically set in. Yes, there were offerings by the great Stephen Sondheim (who seemed to be the only one with a defibrillator on the heart of the Golden Age, keeping it from disappearing into the great beyond by sheer willpower) and Andrew Lloyd Webber, who was redefining the genre with his chimera of musical theater and spectacle.

Webber’s “McMusical” left its DNA not only on practically every show that’s come after but also on how Broadway’s economics work. Webber heralded (and potentially helped create) an era where new American musicals were less likely to be created by Americans or even originate in America.

Despite the success of several rock musicals in the ’60s and ’70s (namely “Hair” and “Godspell”), Broadway had never really been integrated with pop culture the way it had historically been. The generational disparity of the era was exemplified by the fact that the original “Hello Dolly” and “Hair” were running successfully on Broadway simultaneously but with totally different audiences. It seemed the two would never meet again.

In the ’80s and into the early ’90s, the line that had always existed on Broadway between “high-brow” and “popular” entertainment was more pronounced than ever. You could either see “intellectual genius” (like “Sunday in the Park With George” that to this day divides people (try saying, “How do you feel about the second act of ‘Sunday’” at a certain kind of party and your evening is gone…) and never became a mainstay of the cultural zeitgeist however much it advanced the form of Musical Theater), or a spectacular evening of “Wow”!

Perhaps one reason behind the lack of impactful musicals in this era is the fact that the entertainment world lost practically an entire generation of artists to the AIDS crisis. Take, for just one example, Michael Bennett, who revolutionized Broadway with “A Chorus Line” in 1976. Bennett passed away in 1987 at just 44 years old. The “old guard” was starting to pass away too – for example, Bob Fosse, who died in 1987 at 60. Who would train the young generation of Broadway hopefuls starting to set their sights on coming to New York?

And with ticket prices climbing… Broadway was becoming entirely inaccessible for the masses… Infamously, in the 1981 pro-shot recording of the original “Pippin,” the Leading Player says (while looking at the front audience members who held the most expensive tickets), “You don’t want to disappoint all these people at 25 dollars a seat now, do you?! In 1988, the top ticket price at Phantom of the Opera’s opening night in New York was $50… Doubling in just seven years)

But…

If you were to have attended a party in the East Village of New York City around this time (yes, one of the kinds where you probably shouldn’t bring up the second act of “Sunday” unless that’s how you wanted to spend the rest of your night), you probably would have encountered a young man named Jon. And if you were to ask Jon what he did, he would look you dead in the eye and answer completely deadpan and without hesitation:

“I’m the future of the American Musical Theater.”

It was a notorious anecdote people would share for days after. “Can you believe what that wacky guy at the party said?”

But it turns out he was right.

Jonathan Larson changed the face of musical theater. And he did it with one show.

“Rent.”

It’s impossible to talk about “Rent” or its impact without talking about Larson himself.

Jonathan Larson

Larson went to college with the intention of being a performer… but he always wrote. When he later asked Stephen Sondheim if he should pursue acting or writing, Sondheim responded, “Well, there are a lot fewer starving musical theater writers than there are starving actors.” So Larsen decided to go all in on writing.

Specifically, Larson wanted to write for his generation. He grew up on show tunes and popular music and wanted to make musical theater accessible to his generation. He lived in the East Village and worked at a local diner, barely making ends meet, spending all his money on rent, and getting readings up of his shows. He spent most of his adult life working on a musical called “Superbia”… he’d wanted to adapt “1984” into a musical, but when he couldn’t get the rights, he created his dystopian tale.

I was the associate producer on the Library of Congress’s Songwriter Series – including “Jonathan Sings Larson.” I had the honor of working with the Larson estate, including watching videos of the original workshop of “Superbia” – which Larson financed himself at a theater that no longer exists in the Village. It featured such (now) well-known artists as Roger Bart and Valarie Pettiford, who, at the time, were just Jon’s friends (Larson actually went on to write the role of Roger in “Rent” for Roger Bart – who turned it down, wanting to branch out into different kinds of roles, and push for work in commercial theater.) “Superbia” remains one of my favorite musical theater shows I’ve ever seen.

But let’s just say it would be ahead of its time TODAY. I believe it was brilliant and terrifyingly prescient. But in the late ’80s, no one knew what to do with it. (I’m still waiting for it to come to the stage. It’s been caught up in rights issues for decades, and this is me on my soapbox saying it needs to be seen by the public!)

Jonathan fought hard for “Superbia” but was frustrated by the disparate feedback he was getting. The general consensus seemed to be that Larson was a remarkable “promising young talent” but that this particular piece was just too much(Larson would go on to say, “I feel like I’ve been ‘promising’ so long, I’m starting to break the promise.”).

A breakthrough seemed to happen when Larson was given a workshop on “Superbia” at Playwrights Horizons – at the time, the premier off-Broadway theater that had launched some of the most famous and important new musicals in recent memory (including “Sunday in the Park With George.”) But the workshop was a battle from the word go – one big reason being that Larson was told he could only use a piano… a huge disservice when you’re trying to revolutionize the American musical rock score.

First, he was told that Equity wouldn’t allow more instruments, and then he was told it was an issue with the theater… he finally got permission to have drums for one number – and apparently, that was the only time in the whole workshop the show really came to life.

Staring down the barrel of entering his thirties with nothing to show for the years of work he’d put on “Superbia,” Larson wrote a “one man rock opera” that he called “30/90,” and we know today as “tick…tick…BOOM.” “Superbia” was too big? Well, this was one man and a couple of instruments. “Superbia” was too “out there”? This was about a struggling artist having to decide what to do with the rest of his life as he left his twenties behind him.

But this show didn’t take off either.

Around this time, Larson was approached by someone (I believe someone from Playwrights) who knew of a writer who wanted to do a contemporary adaptation of the Opera “La Bohème” and was looking for a composer. Larson began collaborating on the piece but found that he was ultimately more passionate about the material than the original writer. He got permission to take over as the sole writer on the show – sealing the copyright transfer with an agreement written and signed on the back of a napkin.

“La Bohème” was ripe for a contemporary adaptation (not to mention the fact that Larson was writing it on the cusp of the 100th anniversary of its premiere.) “La Bohème” tells the story of struggling artists facing an economic crisis and rampant illness – mainly in the form of tuberculosis, which the principal character Mimi dies from. In contemporary New York City, artists were facing gentrification and housing displacement, economic crisis, and AIDS – which killed many people close to Larson (though, contrary to what some thought at the time, it was not what killed Larson himself.)

Larson used to host “Peasant’s Feasts” for his friends around the holidays and hosted one with the cast of the workshop of “Rent” before they went into production. He told them stories about his friends who had died from AIDS (and are named in the show – the characters in the Life Support meetings are, quite literally, Larson’s friends who had passed away, and included both straight and gay people from all different walks of life.)

He talked to the cast about the fact that they were playing his friends – which included people in the gay community, drag queens, women, and those from other marginalized groups – while he was a straight man facing the fact that he was the lucky one who hadn’t gotten HIV but was left being the sole survivor and watching those he loved die – while no one in a position of power seemed to be doing anything about it.

Larson wanted to show that musical theater could still speak to real people and the real world they were living in. He wanted to make it vital and immediate again and introduce sounds that were, at the time, only heard in popular music.

When the show was done, he rode around the city on his bike, dropping off cover letters and demo tracks with theaters he hoped would give the show a chance.

One did.

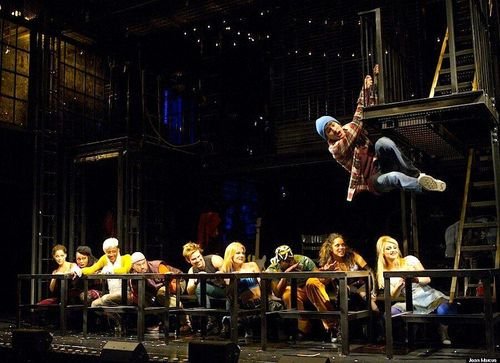

New York Theater Workshop (now known as one of the most important off-Broadway theaters for developing new works. It is, for example, where the current hit “Hadestown” was incubated) gave Larson a workshop on “Rent.” They cast the show with all young, unknown, non-Broadway (and largely “musical theater”) performers and set about figuring out the show. There was a lot of work to be done. (In the original draft, Mimi had a full-on dream ballet (Larson’s attempt to incorporate the classic trope into a modern show… in this instance unsuccessfully…) no one could quite figure out what to do with “Seasons of Love”)

Throughout the rehearsal process, Larson wasn’t feeling well. He went to the hospital and ER several times. He was told he “had the flu” and needed to rest each time. That he was under too much stress, and many would later say that his financial situation (and potential lack of insurance) contributed to his poor care. He managed to attend the final preview performance of “Rent” – where he was interviewed for a feature in the New York Times who wanted to do a profile on the show given that “Rent”’s opening at NYTW in February 1996 coincided almost to the day with the 100th anniversary of the Italian premiere of “La Bohème”. He went home that night, made some tea, and died of an aortic embolism. Had his condition been diagnosed earlier, his life could have easily been saved.

The entire “Rent” team was stunned. Larson’s parents were flying into NYC to attend the opening and then heard the horrible news. The decision was made to continue with the performance but to do it more as a reading. But by the time they got to the end of Act One’s “La Vie Bohème,” the cast couldn’t stand still anymore. They moved their chairs and started doing the show full out.

“Rent” was an instant hit, and it was soon announced that the show would transfer to Broadway. But the problem was… there were still dramaturgical things that needed to be addressed with the show… but the writer was no longer there to weigh in. Feeling that it would be worse to make changes without Larson than to move the show as it was (flaws and all), the version that performed at NYTW was the version that opened on Broadway.

And it changed everything.

I remember the first time I discovered “Rent.” I was a kid and spent the night at a friend’s house. It was late, and my friend turned to me and said, “There’s something you have to hear.” We sat on the floor of her bedroom, and she put on the cast album - how someone might play you the new album from their favorite niche band they’re secretly obsessed with. I remember the explosive first chords of the title song… and my ears couldn’t comprehend what they were hearing. I had literally never heard anything like it before.

I remember how stunning, vital, and immediate it felt. My shock at hearing beepers being used, let alone addressed in the lyrics of a Broadway score. The frequent discussion of HIV/AIDS, it was as if someone had taken life right NOW and put it onstage. It’s rare nowadays that shows see a commercial production while the things they were written about and discussing are still urgently in the moment (the length of development now means most “hip new musicals” don’t end up seeing the light of day until ten years after they WERE “hip” and “new”.)

“Rent” was the breakthrough rock musical that bridged the generational gap (something “Hair” and “Jesus Christ Superstar” never quite did in their heyday.) But now the young people who had loved “Hair” were parents – sharing “Rent” with their children.

The rock musical wasn’t dividing generations this time – it was uniting them.

“Rent” was posthumously nominated for ten Tony Awards, winning four (Best Musical, Best Book, Best Performance by a Featured Actor, and Best Score), and became one of the only musicals in history to win the Pulitzer Prize for Drama. It went on to be performed in twenty-five different languages, from Greek to Korean. It featured a diverse cast of actors and told the stories of marginalized groups at a time when that was an impossible sell in the commercial theater. The show incorporated musical styles never heard in a Broadway score and was the first show in decades to break into the popular music scene.

There are many small ways that “Rent” changed the Broadway landscape, too. For example, it launched the career of Bernie Telsey Casting… “Rent” required very specific things from its performers, so it couldn’t be cast using traditional methods or from the performer files of most casting directors. Telsey sought out unusual, underground talent – looking to actual East Village artists, indie singers, and those off the beaten path.

They did such a good job casting the show that they became the go-to casting directors if you needed pop-rock musical theater performers (which basically became a new genre of the artist) and all-around difficult casting projects. Today Telsey & Co is one of the biggest casting agencies in the world.

“Rent” also invented the idea and policy of rush tickets. Trying to reconcile the fact that “Rent” was a show about a largely impoverished, struggling demographic with the fact that it was going to be performing on Broadway – an arena traditionally only accessible to the top echelons, they decided to reserve a certain number of tickets – specifically in the first few rows of the orchestra, that would be sold the day of at an extremely discounted price.

This meant that the show was now accessible to those who might otherwise never have been able to come to Broadway, and it established a remarkable community of those who would literally camp out in front of the theater to be guaranteed a rush ticket the next morning. Soon, most Broadway shows began implementing some rush policy (though now the cost of rush tickets has ballooned to such a degree that they’re the cost of an inexpensive regular ticket…)

Part of the tragedy of Larson’s death was that not only did he not get to see his success, but one can only imagine how much more he would have changed the landscape of musical theater if he had lived and finally had the platform to explore his brilliant, innovative ideas fully. If he were still alive, Larson would be in his mid-sixties. It’s tragic to think how many songs and stories we’ve never heard… and imagine what the American musical theater could have been with his continued presence.

As noted by PBS: “’Rent’ achieved Larson’s ambition of updating musical theater and making it socially and personally relevant to a younger audience.”

“In these dangerous times, where it seems that the world is ripping apart at the seams, we can all learn how to survive from those who stare death squarely in the face every day and should reach out to each other and bond as a community, rather than hide from the terrors of life at the end of the millennium.” – Jonathan Larson