Priced Out of the Tragedy: The Real Irony of Paying $900 to See 'Othello' on Broadway

Sara Krulwich/The New York Times

by Chris Peterson, OnStage Blog Founder

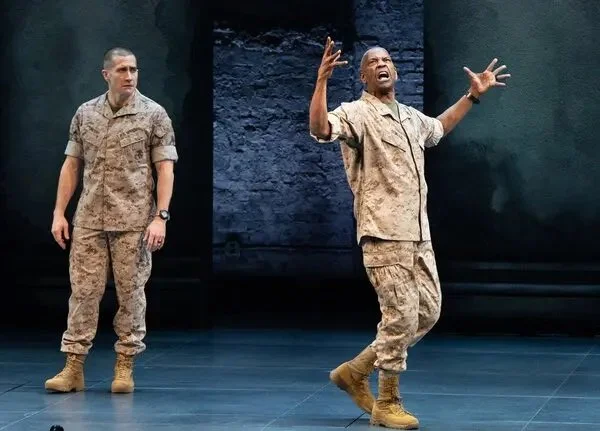

When it was announced that Denzel Washington would be returning to Broadway in the title role of Othello, I lit up. That familiar thrill kicked in — the kind of announcement that makes you stop everything and say, “Well, I have to be there.” Add in Kenny Leon as director and Jake Gyllenhaal as Iago? Forget it. That’s not just theatre — that’s an event. It felt like one of those rare moments when Broadway grabs the world’s attention and says, “Watch this.”

And then… the ticket prices dropped.

Premium seats: $900.

Nine. Hundred. Dollars.

For Othello.

Look, I love theatre. I love it enough to have justified ticket prices that made my credit card sweat. And Denzel is — without a doubt — one of the most captivating performers of our time. But when I saw that number, something shifted. Not because he’s not worth it, but because it made me ask: Who exactly is this production for?

The timing couldn’t be more poetic — or more uncomfortable. Othello is literally about a man being othered, doubted, and manipulated by the very system he’s worked tirelessly to serve. It’s a play about being invited into the room… but never fully welcomed. And now, the production itself is following a not-so-different script.

What does it mean when this story, with this cast, becomes financially out of reach for so many? What happens when the people who would connect most deeply to the themes of the play — the ones who see themselves in Othello — can’t afford to be in the room?

Broadway’s pricing problem isn’t new. Rush tickets, standing room, lotteries — they all try to soften the blow. But a $900 top price doesn’t just stretch budgets. It sends a message. It tells you who this night is really for.

And maybe it wouldn’t sting so much if it weren’t Othello. Because this isn’t a commercial comedy or a pop musical. This is a brutal, deeply relevant tragedy about what it means to navigate power as an outsider. About what it costs to constantly prove your worth. And now, the irony is that we’re telling that story while keeping so many outsiders... outside.

Othello’s downfall comes from believing he belongs in a world that, ultimately, won’t protect him. He trusts the system. He plays by its rules. And still, he’s undone by it. Now, centuries later, we’re watching that same story unfold in real time — not just on stage, but in the structure around it.

Theatre, at its best, is about gathering. Feeling. Witnessing together. But this production, however unintentional, is becoming something else. Not a gathering. A gala. A luxury experience for those who can afford the exclusivity.

And look — if you have the means to go, go. Truly. Witness it. Celebrate it. Tell me all about it. But let’s not pretend this kind of access isn’t part of the story we’re telling.

Because the true tragedy might not be what happens on stage — it’s that so many people who should see it… won’t get the chance.

The irony of Othello isn’t just in the script. It’s in the system that surrounds it.