Explore Hal Prince's Innovations at Lincoln Center Library

Aaron Netsky

In the Company of Harold Prince, the new exhibit at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center, was already in the works when Hal Prince died on July 31st of this year at the age of 91. His death probably didn’t change much; the show was likely already packed to the gills with highlights and nuggets of his 60+ year career in the theatre, although perhaps it makes the part about his legacy a little more poignant. Indeed, if I hadn’t known any better, I would have found it hard to believe that the producer of “The Pajama Game,” “West Side Story,” and “A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum,” and director of some of Stephen Sondheim and Andrew Lloyd Webber’s most iconic musicals, from “Follies” to “Phantom,” and much, much more, was still alive and working with writers old and new. It would be like believing Charlotte Brontë was still writing novels or Frank Lloyd Wright was still designing buildings, he had been at it for so long and his influence was so widespread. Sadly, the exhibit is perfectly timed, but to visit it is not a grim or upsetting experience. It is a celebration of the stage he loved so much.

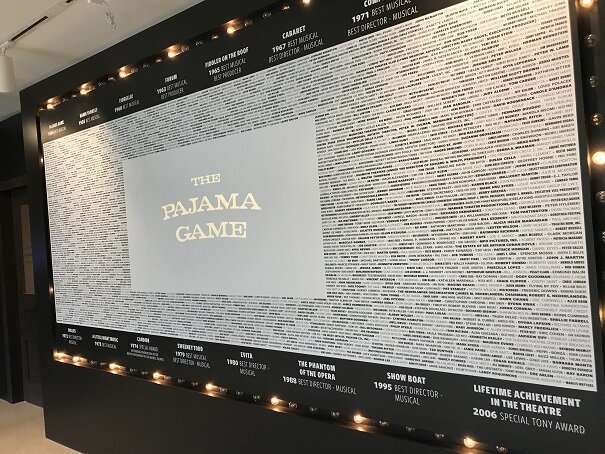

The visitor walks in, past the marquee-like welcoming wall that announces Prince’s most famous and important shows and lists his Tony Awards, to a kind of recreation of his workspace, complete with desk, chair, lamp, papers, and a phone that rings every so often but I wasn’t sure if I was allowed to pick up and perhaps receive a recorded message from the man himself (parts of the exhibit are interactive). On the walls are artifacts like the correspondence that landed him an early theatre job in 1948, stage managing a play called “Just David” in Maine, and an Al Hirschfeld caricature (there must always be at least one at such an exhibit), depicting a rehearsal of the play “Say, Darling,” in which Robert Morse played what many believe was a version of Prince during the period when he was producing “The Pajama Game.”

In the next room are displays devoted to some of Prince’s earlier productions, featuring set renderings and models from “Fiddler on the Roof,” costume designs from “She Loves Me,” and promotional materials from “Baker Street.” There are also some amusing photographs, for instance, one of Barbara Cook surrounded by Harbison Dairies ice cream, in a cross-promotional effort described by Prince in an adjacent letter (in “She Loves Me,” Cook sang an ebullient song about ice cream), and Bob Holiday getting his bicep measured for his Superman costume for “It’s a Bird… It’s a Plane… It’s Superman.” Nearby are pieces that layout Prince’s efforts to not just make theatre, but make it more accessible and more affordable. Items and video having to do with the Phoenix Repertory Theatre and Taganka Theatre in Russia go into Prince’s development as a director, and shed some light on how he arrived at the “concept musical.”

The real meat (pie) for most visitors, in all likelihood, and the dominant presences in the exhibit, are the displays having to do with Prince’s collaborations with Sondheim and Webber, which include a reproduction of the Lovett’s Pie Shop set, from “Sweeney Todd,” the organ, boat, and several Masquerade costumes from “The Phantom of the Opera,” and many, many set models and costume designs. Footage from several of these shows is playing on the walls, mostly with headphones (though as soon as I could no longer hear that phone I started to hear the looped portion of the finale of “Phantom” playing in the last room of the exhibit; I can identify Michael Crawford’s voice from twice as many rooms away). Having recently read a biography of Prince and being in the midst of one about Sondheim, having these physical manifestations of the history I’ve been immersed in was a great thrill, but one needn’t have done their research to fully appreciate the beauty of the design of Commodore Perry’s ship from “Pacific Overtures,” the haunting depth of the decaying theatre set from “Follies,” or the simplicity of one of Evita’s dresses.

Of course, what I’ve described here just scratches the surface. Much room is given to Prince’s frequent collaborator on the production side of things, Ruth Mitchell. In the “Cabaret” section, next to a ghostly projection of Joel Grey as the Emcee, is a reproduction of the 1966 “LIFE” magazine “White Backlash” article, about racists in Chicago, that Prince brought to the first rehearsal to show that the feeling that gave rise to the Nazis was not unique to the time and place in which “Cabaret” is set. There is an interview with Prince from when he mounted a production of “Show Boat,” widely considered to be the first true piece of musical theatre, and therefore, really, a natural choice for him to revive and put his own stamp on in 1994. So very, very much to see. Planning to see a show? Chances are it owes its existence at least in some part to something Hal Prince did, some innovation he made with one of his collaborators, and so a visit to this exhibit, which is open from now until March 31st, 2020, pairs perfectly with any production.

Aaron Netsky (@AaronNetsky on Twitter, @aaron_netsky on Instagram) is a singer, writer, actor, and all-around theatre professional who has worked off and off-off Broadway and had writing published on AtlasObscura.com, TheHumanist.com, Slate.com, StageLightMagazine.com, and ThoughtCatalog.com, as well as his own blogs, Cantonaut (http://cantonaut.blogspot.com) and 366 Musicals (https://366days366musicals.tumblr.com), and his Medium account.