Actor Cooper Howell Alleges Racist Treatment Backstage at Disney Park 'Frozen' Show

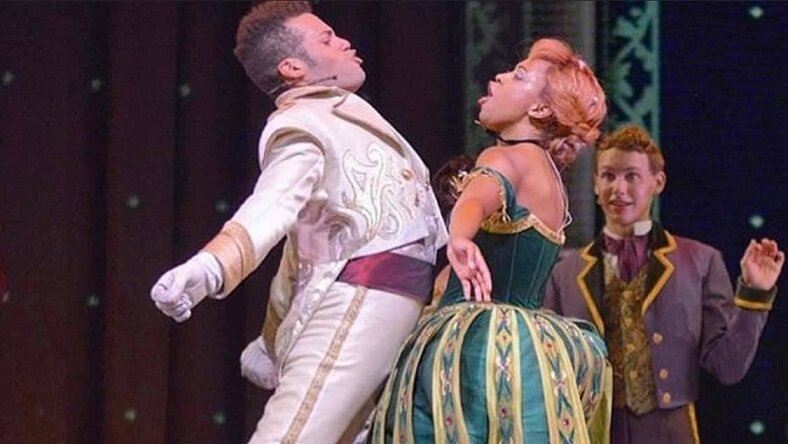

Cooper Howell in Frozen: Live at the Hyperion

Meg Masseron

As our country begins to confront the systemic racism and racial injustice that is still ingrained into our society, the theatre industry has begun a reckoning with its own instances of racism. A handful of black actors have come forward and shared their experiences, including Cooper Howell, who took to Facebook to detail the instances of racism he endured while performing as Prince Hans in Frozen: Live at the Hyperion.

Howell described his experience playing Prince Hans as both “heaven and hell.” Initially, Howell felt that he was in a largely positive environment, particularly due to his original director, Liesl Tommy. Tommy did not stay with the production as long as Howell, thus leaving him with a new director later on.

Howell expressed in his writing that throughout his life, he was repeatedly reminded both as a person and a performer that he was an “other,” whether it was by high school drama teachers announcing that they could “finally do black shows,” or people in his home state of Utah frequently commenting that he was the “whitest person they ever knew.” These racial microaggressions, like they do for many other emerging black performers, made it clear to Howell that he was seen and treated differently than his white and non-black peers.

When Howell was cast as Prince Hans in Frozen: Live at the Hyperion, he described being astonished by the fact that he was finally being valued for who he was as a performer and a person: “What was being prized was Howell, my talent, not my skin color that I never asked for,” he wrote. Howell also attested that Tommy ensured people of color felt included, comfortable and respected. “Liesel made sure, almost overly sure, that the POC’s in the cast felt equal,” he wrote. “The kingdom of Arendelle, after all, is a make-believe place. It can be whatever. From having Disney executives come and tell us that they were happy to have us here...we were made to feel overly welcome playing the parts we were playing...we felt seen as talent and not commodities.”

By showing Tommy’s commitment to fostering a safe environment for people of color within the cast, Howell suggests an ideal picture of what theatre artists can do to reduce racism both backstage and onstage. Howell’s personal testimony of the dark side of the theatre industry and its covert biases, however, showed what should not be happening, yet was still a reality for himself and his coworkers.

After Tommy departed from Frozen: Live at the Hyperion, she was replaced by Roger Castellano as show director. Howell describes in his writing that, from his very first day, Castellano’s goal was to “change the show.” Howell adds that specifically what Castellano wanted to change was unclear, or why any changes were necessary. This was just the tip of the iceberg, of what would become a much larger debacle for Howell and his coworkers of color.

During Castellano’s first note session with the cast, Howell claims that Castellano singled him and his black co-star who played Anna, Domonique Paton out, escorting them into a private room. Howell notes that earlier that day, he had performed the show with a different actress playing Anna, and the actress was white. According to Howell, Castellano had not initiated a private meeting for Howell and the white actress, only for Howell and Paton. In Castellano’s meeting with Howell and Paton, Howell claims that Castellano told them: “when the two of you perform the show together, it’s too urban.”

The only rationale Howell could come up with, Howell explains in his writing, was that perhaps Castellano was referring to an 8-count synchronized dance sequence during Paton and Howell’s scene, but why would Castellano use the word “urban,” rather than “contemporary” or “modern?” Castellano’s word choice suggested to Howell that this was not in reference to the style of dance, but the color of Howell and Paton’s skin.

Howell asked Castellano to elaborate on his word choice. Howell claims that Castellano simply shrugged and said “you can figure that out, you’re smart.”

Howell explains that his “every moment onstage afterward became about the optics of being a POC in that show.”

In the weeks following this meeting, Howell noticed that he and Paton received a copious amount of notes. Howell quantifies the amount as being ten times that of their coworkers. Howell describes that the notes were about a myriad of trivial things, such as how they held hands, if their inflection went up or down on a singular word, or which side of the couch they leaned on. He expresses that while other cast members got a simple comment or suggestion and a “try doing this next time, goodbye,” Howell’s note sessions would sometimes last ten to fifteen minutes.

The hyper-criticism soon turned to harassment, Howell alleges, when he began receiving notes about his groin.

Howell described these note sessions as “penis sessions,” which were given in private rooms without another stage manager present. In these meetings, Howell claims Castellano would berate Howell for his pants being too tight, and outlining his groin too severely. Howell noticed the double standard when Castellano demanded that Howell purchase a dance belt to help conceal his groin in uncomfortable and disrespectful private meetings, while his white co-stars were simply given dance belts for free without these invasive conversations. Howell was repeatedly told that it was “his fault” and “his responsibility” to purchase a dance belt. At one point, Castellano even screamed at Howell in front of all of his co-stars during lunch about how unprofessional he was and how if he did not purchase a dance belt, he did not deserve to be in the cast anymore, Howell claims.

Howell describes in his writing that it became clear to him that he was being targeted and singled out against his coworkers, and the common denominator was the color of his skin. During this period, Howell writes that he went to every stage manager in the building to tell them about his experiences, and they all told him to write a complaint that would be sent to “HR.”

As time went on, Howell was left unsure what “HR” even was, because he never received a response from them. Howell eventually discovered where HR was in Disneyland and met with the head of HR personally. He asked her if she ever received any of his reports, and she claimed she’d never received a single report from the Hyperion in all of its history. He was then asked to fill out another form.

With no protection from the stage managers and little support from his cast members, who feared that if they testified as witnesses they would lose their job, Howell eventually quit his job at the Hyperion. Howell wrote that the wonderful experience he initially had that caused him to finally feel celebrated for who he was as a performer was short-lived, and never occurred again in his career. “This one time four years ago I got to feel something other than my color for the first and only time in my professional career. It lasted from about March 2016 to July 2016, and never again since.”

Onstage Blog reached out to Roger Castellano for comment, but he was unresponsive.

Howell’s story gives us a lot to digest as an industry and a community, and on what behaviors we need to shut down within the theatre world, and what new behaviors of inclusivity and respect that we need to adopt. More importantly, Howell’s story makes it evident that, at least in the case of the Hyperion (although many other recently revealed stories indicate that this is common within many theatre companies), there is not enough protection from harassment, at all, for people of color in theatre, and not enough support to help them find justice in these situations.

As the theatre industry continues to stand still in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, there is time to dismantle the systems of white privilege and racism within the industry and to listen to black voices and let them lead us into a much more inclusive and unified future.