Off-Broadway Review: 'The Profane'

Melissa Slaughter

- OnStage New York Critic

Profane: (noun; of person or thing) not respectful of orthodox religion practice; irreverent

(Verb) to treat something sacred with disrespect

With these definitions in mind, The Profane is a play that deals in dualities, and binaries. The play introduces an array of ideologies: fundamentalism, liberalism, feminism, classism, patriarchy, on and on and on. What is sacred to one person is profane to another. The basic premise of the play is that the daughter of a prominent, liberal-minded novelist, brings home her fiancé. Her family is first generation Middle Eastern immigrants as are his. Her family is militantly secular; his is orthodox. Chaos ensues.

Since the play focuses on binaries, let's do the same, shall we?

THE GOOD:

1- In the world of #OscarsSoWhite, of literally attempting to build walls, and of representations problems everywhere, Playwrights Horizons has tried to be a place of inclusion. A place where stories of POC can come to thrive, or fail, or workshop, or take risks. The Profane is a fine example of Playwrights keeping to their mission to"meet the individual needs of each writer in order to further develop their work"and that must be applauded.

2 - We have a story completely populated by people of color, which is not only refreshing, but also important. There were 7 actors onstage showcased in unexpected ways. Sam's father (Ramsey Faragallah) was a true delight and standout. And I would gladly see any of these actors perform again.

3 - The set, large and all encompassing, not only did its jobs in highlighting the virtues of each household. They became almost characters unto themselves. One is a deluge of literature and art, with a dictionary at its core and no family photos to be seen. The other is sparse, but bright and welcoming, a Quran the only text in sight and family photos as some of the few decorations. Scenic designer Takeshi Kata's work perfectly let's audiences know everything there is to know about each family.

4 - I believe that while writers should write what they know, they should not be limited to writing only for their race. Julia Cho shouldn't be limited to writing only Asian plays, as witnessed by her play A Language of Their Own. Kimber Lee's Brownsville Song is an exquisite look at an African-American family in Brooklyn. Tony Kushner wrote Belize into Angels in America, one of my favorite plays of all time.

So while I certainly want to know what is Zayd Dohrn's affiliation with Muslim culture, I also applaud him for taking a risk to showcase a culture that is not his, and for not writing another white family drama.

But does he succeed?

THE BAD:

The biggest problem in my viewing of the show is that these two families encompassed two different ideologies and never the twain did meet. These people weren't people; they were vehicles for differing views. And while this conflict is usually the concept behind great storytelling, the inherent problem of The Profane is that these characters are ideals only.

Except for very superficial moments, I never understood what each character wanted from each other and what they needed for themselves. And I also did not get a sense of urgency from any of them. Why must the kids get married now? Why must they meet the other family now? Why tell secrets now? It's a very fundamental part of character development, and it wasn't present in this script.

The characters of The Profane were collections of archetypes, or maybe stereotypes, bashing against each other for an hour and 45 minutes. There's little attempt at compromise, at listening, or at finding a common ground. And in a world where we should understand that much of humanity lives on a spectrum, Dohrn throws out the two most binary points of view, juxtaposes their stereotypes, and calls it a day. Honestly, it's a little too easy and a little lazy. The script is a lot of tell, and very little show. Plot holes are left gaping open and there are several of Chekov's guns left out and untouched. The hard work of listening and understanding almost never happens.

Raif (Ali Reza Farahnakian), the "liberal" father, in particular was an issue for me. At some point he became a walking soapbox of his own dogma. Every time he opened his mouth, I knew there would be a monologue of wandering postulations of his own makings and his own convenience. He is a series of quotes and quips, thinking himself an intellect and a man of the people.

What he really is is a self-loathing immigrant. That tension, between Raif's idea of himself and his idea of his homeland, is the most palpable. Yet, like many of the themes introduced, it's never truly explored. And since the narrative revolves around Raif, everyone must react to him. But if Raif isn't settled as a character, than really, what can anyone else react to?

I don't know if the fault lies with the actor, the writer, or the director. Maybe it's all three. Kip Fagan's direction seems almost too light. The play lives in such a cerebral places that it never really settles into itself. It's all ideas that float above the audience and the players. Nothing is grounded. So then the thoughts don't land, the language gets old, and the rhetoric gets tiresome.

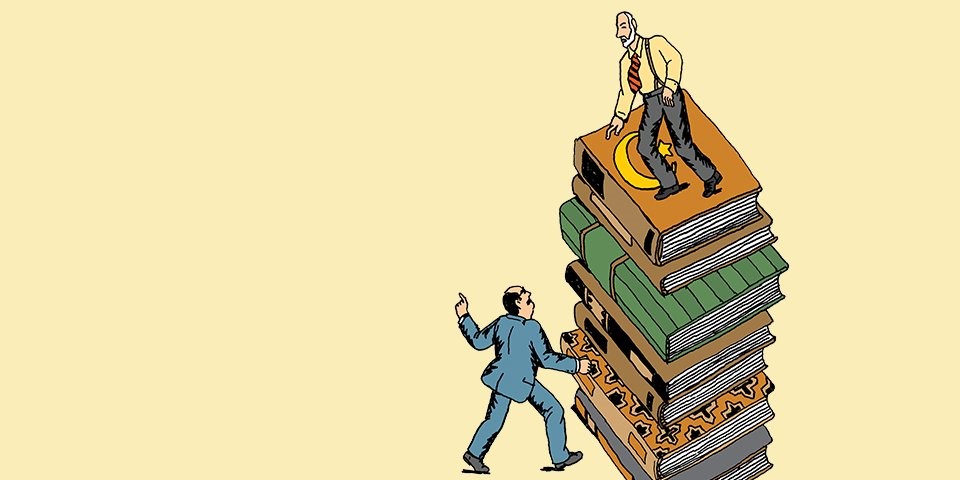

In the end, the program's illustration says it all: two men separated by books and knowledge shaking their fingers at one another. And there's no way foreseeable for them to see eye to eye.

THE MIDDLE GROUND:

Again, I applaud Playwrights for putting on this piece; I applaud Zayd for writing it in the first place.

Now I implore them both: do more. You've made it past step one. You put on the show. But the work has only just begun. Now go deeper. Ask more questions. Clarify the themes and maybe hack one or two away. Kill your darlings. Fail better.

Because I can't help but wonder who did Playwrights passed over to put up The Profane? Which Persian, Arab or Muslim playwright was passed over so Zayd Dohrn could have his play on the stage?